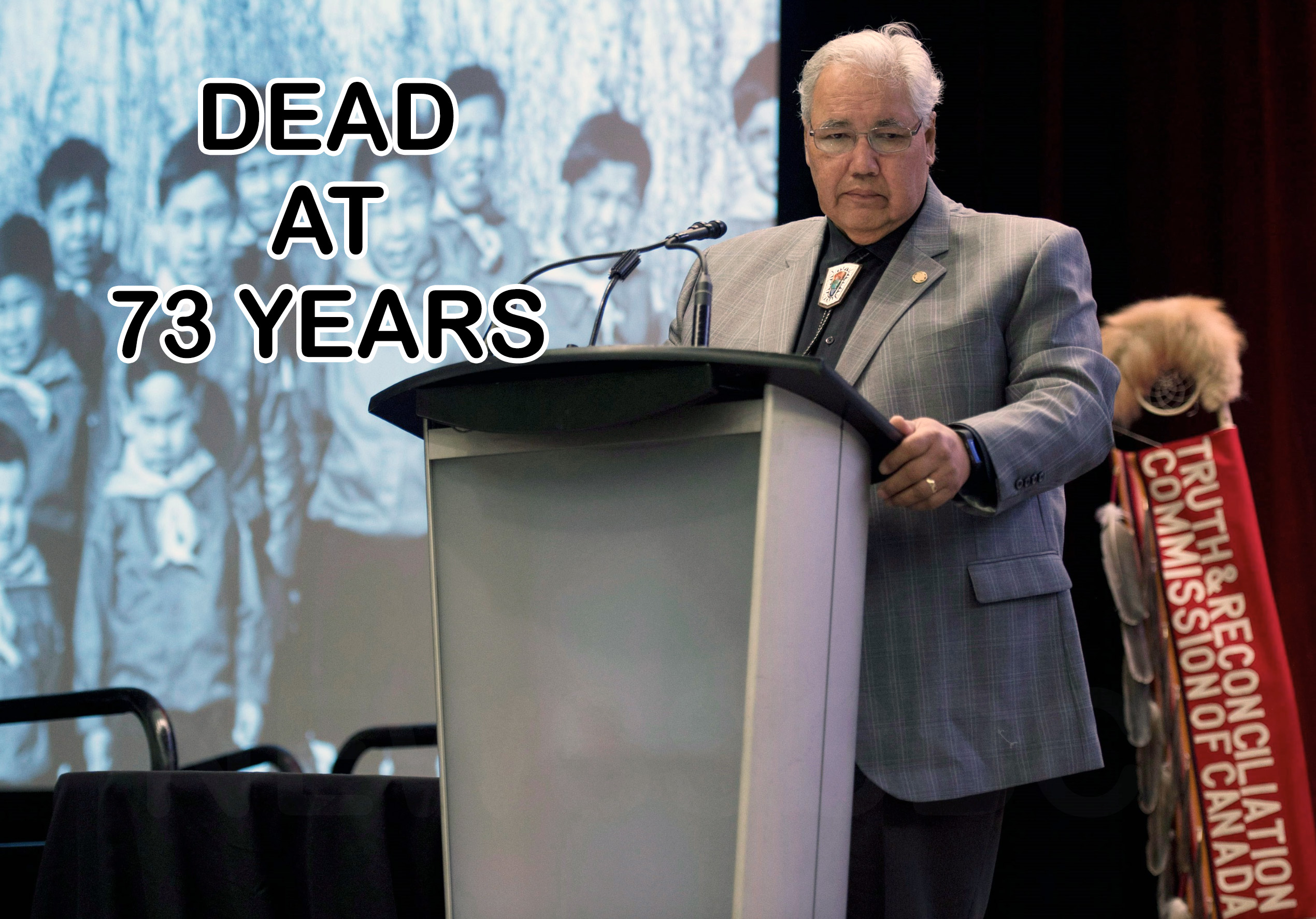

Murray Sinclair, Former Senator And Chair of The Truth And Reconciliation Commission Dead At 73 Years Old

Murray Sinclair died “peacefully, surrounded by his family,” in Winnipeg on Monday after several months of being hospitalized from congestive heart failure.

His influence resonated across the country and beyond, from Survivors of Residential Schools to law students to those appearing before him. He was an exceptional listener who knew that each person carried dignity, his family said in the statement.

Moreover, Sinclair was an exemplary public servant throughout his entire life. He was the first Indigenous judge appointed to the bench in Manitoba and only the second in Canada as well. A respected leader within the nation of the Anishinaabe in the justice department, his legacy’s impact will continue to ripple strongly into Indigenous communities for decades to come.

Mr. Turpel-Lafond has been a leading figure in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, serving as its Chair alongside Chief Wilton Littlechild and Marie Wilson. Their final report not only recorded the history and legacy of Indian Residential School survivors in Canada but also ultimately presented 94 Calls to Action, which have since been guiding Canada on its path toward reconciliation with Indigenous peoples.

Murray Sinclair was a devoted husband, father and grandfather. He is survived by his five children, Jazek, Neganowidam (James), Dine, Kizhay and Miskodagaginikwe, and many grandchildren. He lost his wife Katherine to cancer in June.

Tributes to Sinclair began to pour in from across the country.

In the Ontario Legislature this Monday morning, the news was revealed by New Democrat MPP Sol Mamakwa in stunned tones, which led to a drop into a moment of silence.

The Governor General Mary Simon did the same: “We mourn the loss of a friend and important Canadian leader who was a tireless advocate for human rights, justice, and truth.” He had an empathetic and insightful spirit that could inspire and touch many people.”

Table of Contents

Early Life and Career Beginning

Murray Sinclair lost his mother, Florence, to a stroke when he was an year old, thus he and all three siblings, Richard, Buddy, and Diane, were brought up by his grandparents, Catherine and Jim Sinclair. It was his grandma, originally Métis-Saulteaux from Fort Alexander, who taught him to speak Michif.

Sinclair’s abilities shone out even in his very early life. During his teens, he was part of the 6th Jim Whitecross Royal Canadian Air Cadet Squadron and an honoree of that squadron for being of a remarkable leading capability. At age sixteen and a student, he was named the best athlete, and class valedictorian upon graduation from high school at Selkirk College in 1968.

He then went on to study sociology and history at the University of Winnipeg. After two years, Sinclair laid work off to tend for his ailing grandmother and then worked at the Indian and Métis Friendship Centre in Selkirk. Later, he became the Vice-President of Interlake Region until 1973 for the Manitoba Metis Federation. He pursued further education until 1975 and then went on to law school at the University of Manitoba.

Over a period of 25 years Sinclair practised law in areas including civil and criminal litigation, Indigenous law, and human rights, serving as legal counsel to many First Nations, Indigenous child welfare agencies, Métis organizations, and Indigenous businesses, and also represented the Manitoba Human Rights Commission. In 1981 he became a legal advisor for the Union of Manitoba Chiefs and taught Indigenous law both at the University of Manitoba and through lecturing across Canada.

It was an activist from the Gitxsan tribe, Cindy Blackstock, and the Executive Director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, that first brought Sinclair’s work to Indigenous justice. Murray was often the first but he never marched to the drum of being first. As Blackstock recalls, he was the first so others could be second and third and fourth and so on.

Blackstock added, “Murray was at all times a beacon for fairness and respect, an optimist who vowed to work tirelessly for today’s and tomorrow’s children.”.

Murray Sinclair was also a cultural leader within the Anishinaabe community, along with his lifetime partner, Katherine Morriseau Sinclair of St. Rose du Lac, an artist and educator. Blackstock noted that his family was very generous not only in letting us have time with Murray but also as role models through their example.

Murray Sinclair spoke Ojibwe fluently and was from the Fish Clan. He was also an active spiritual leader who led trails for Three Fires Midewiwin Lodge, among other places, with Morriseau Sinclair. Sinclair is a Second-Degree member of the prestigious Midewiwin Society within the Ojibwe.

Murray Sinclair concluded, “Love is the centre of Indigenous knowledge for living life.” Love is the centre of all things – the earth, the water and our relationships. If we start from there and stay close, we will be okay.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Murray Sinclair listened to the testimonies from survivors and those from their families and community for over 6,500 people. He took up a successful, multibillion-dollar fundraiser himself, to help finance the costs of TRC events to ensure many survivors’ participation.

The final groundbreaking report from the Commission named 94 “Calls to Action” in 2015.

As Murray Sinclair said during the closing event in December 2015, Commissioners have been changed by all that they had seen and heard and been told on their journey as they were by the experiences shared with them and with the rest of Canada.

“We cannot say we are the same as we were at the beginning, anymore than this country is now different.”

Meanwhile, in the wake of the release of that report, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said he hoped it would “help heal some of the pain inflicted by the residential school system and begin to restore the trust lost for so long”. He promised to implement all Calls to Action. By 2023 only 13 out of those 94 calls have been fully implemented.

As Murray Sinclair noted during the ceremony, “Let’s remember that we are writing for history, not just for the administration du jour.” This report is to be a long-lasting one, not just in this timely state but also as a guide for future decisions when referred to.

Senate

In 2016, Trudeau named Murray Sinclair to the Senate in April of that same year, making him the 16th Indigenous person to enter the body. Later, he dubbed it “the House of Hope.” Sinclair said, “I’m hopeful about the future in taking up this role and continue being committed to reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians, a cause close to my heart.”

In 2020, following his retirement from the Senate, Murray Sinclair returned to the practice of law by joining Cochrane Saxberg LLP, the largest Indigenous-owned law firm in Manitoba. He left the Senate early in 2021 to become the 15th Chancellor of Queen’s University and the first Indigenous person in that position of chancellor. He was named a Companion of the Order of Canada in 2022 for efforts to “advance truth, justice and reconciliation” and support Indigenous rights.

In June, Murray Sinclair stepped down as Chancellor but remained at Queen’s as a special advisor to the principal on reconciliation.

He put out his memoir, Who We Are: Four Questions for a Life and a Nation, this September, a book about Indigenous knowledge, and a way forward on the path of reconciliation for Canada.

He told Dundas he wrote his story to understand who he was — as an Indigenous man in Canada — and in order to ask readers one question: how their own creation myths intersect with his through four very significant questions.

We are, collectively, a wonderful, yet tangled tale.

This was accompanied by the Order of Manitoba in 2024, in addition to the Distinguished Service Cross he received in 2017.

Murray Sinclair had been suffering from a lot of illnesses throughout his life. He even had a mini stroke back in 2007 but later recalled it as his “wake-up call.” He regained completely and started writing letters in the form of writing the autobiographical account, a diary addressed to his then two-year-old granddaughter Sarah.

Murray Sinclair and Morriseau Sinclair moved into a care home in Winnipeg this past winter. Sinclair was living with a diagnosis of congestive heart failure and lymphedema. Morriseau Sinclair died from cancer this June 27th .

13 thoughts on “Murray Sinclair, Former Senator And Chair of The Truth And Reconciliation Commission Dead At 73 Years Old”